When we started toying with CrossFit in 2008, I’d already been a fitness coach for twelve years. I wrote homework for 5-10 different people every day, with 5-8 workouts per person. I don’t care to do the math, but that’s a lot of workouts, and no one ever saw the same one twice unless they were testing.

I still wasn’t comfortable programming ‘CrossFit’ workouts for another two years. The ‘constantly-varied’ part of What Is CrossFit? didn’t worry me; the problem was that I had no idea what INTENSITY meant until that point. I thought I knew, but CrossFit changed my perspective.

Our workouts may seem random. They’re not. Here’s how I come up with them.

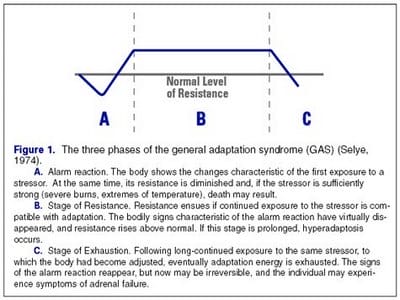

Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome was first pitched in 1936. In general, said Selye, the body adjusts to new stress (like exercise) in three phases. First,the Alarm phase: you get slightly worse as your body tries to figure out how to deal with the new stress. Eventually, you supercompensate: you become smarter, stronger, faster or more fit. When the stress is appropriate, you may become all four. In the third phase-exhaustion-you’ve done too much, or the same thing for too long, and you’re no longer forcing adaptation. Occasionally, newcomers to CrossFit confuse ‘alarm’ with ‘exhaustion,’ and believe that it’s simply too hard for them. Unfortunately, these are the folks who can benefit MOST.

Read more about the biology of stress here.

When you want to calculate how MUCH stress is good, how much is best, and how much is too much, you need a human audience under your complete control. This is why so much of the fitness and sport literature refers to Russian sport science of the 1950s through the 1970s. Russian athletes’ lives were sometimes controlled to the smallest minutia (including when they went to the bathroom, when they ate, and when they had sex.) Much of that research was published in the USSR’s internal Journals of Sport, and some has been translated by Sportivny Press, and others.

We focus on three macro-level ideas from the Russians: progressive overload, periodization, and loading within workouts. Progressive overload is commonly interpreted to mean “do a set of 12, a set of 10, and a set of 8 reps,” but that oversimplification doesn’t do the concept justice. Though it’s the mainstay of popular bodybuilding culture, folks who found fitness through CrossFit are sometimes unfamiliar with the concept. Though just a basic scheme of progressive overload, Starting Strength enjoyed huge popularity for awhile simply because it seemed different from CrossFit.com’s ‘constantly-varied’ programming.

Periodization was popularized in the West by Tudor Bompa. You can read his book, Periodization for Sport, at our gym library. This is linear periodization, in which one can take Selye’s GAS and spread it out over the training year. Athletes progress through alarm and supercompensatory phases in waves: first, fitness (General Physical Preparation,) then Max Strength, then Power, etc., building toward a sport-specific peak.

Medvedev and others modified the linear programming concept to overlap these phases. Athletes maintained GPP year-round, and performed max strength lifts and speed lifts every week. Managing The Training of Weightlifters is a fantastic little book, and you can read it in our gym library, too. Verkhoshansky, Siff, and Zatsiorsky all contributed to our base of knowledge, and we use Prilepin’s Chart to help choose the loads and total load you’ll be lifting all the time.

Louie Simmons, of Westside Barbell, applied the Conjugate Model to powerlifting. Dave Tate summarized the concept in the Periodization Bible series. We use this template for strength training. Why didn’t I just say that in the first place? Because it’s important to know how we came to this spot, and also why we don’t use Louie’s iteration exactly the way he does. Jim Wendler’s 5-3-1 program is a simplified version of the early Westside model; a lot of CrossFit gyms use it because it fits nicely into an hour class. See progressive overload.

Thus is our strength training derived: two heavy days (get stronger,) and two speed/technique days (get better.) Strength plays a large role in our overall objective (get fitter.) I go into a bit more detail here. One final bit on strength training: in the early periodization models, and in Westside, and Wendler and Smolov, fitness is included to serve strength. We include strength training to serve fitness. Being stronger makes you more fit, but it doesn’t replace any of the other nine elements of fitness. It IS more fun than most, and that’s important, but it doesn’t fix any of the other nine.

Strength is the skilled (focused) application of force. While we enjoy any enthusiastic application of force, we can’t ignore the skilled portion: the best way to get a better clean is to increase your skill, not your strength. This has been a very hard lesson to learn: the higher the skill requirement, the less carryover from other lifts. It seems obvious, in hindsight, but it explains why a ginger-headed coach with a 520 deadlift can struggle with a 135 snatch. Pride is a huge impediment to fitness.

For that reason, every workout we coach begins with a warmup appropriate for developing skill. Next is skill-specific training. If you’re on your third year with us, you can still get better at squatting. Athletes who squat competitively can still get better at squatting. So can your grandma. You can also get better at everything. No other program, before CrossFit, had a general skill bias. We want you to get better at everything, and thus improve your fitness.

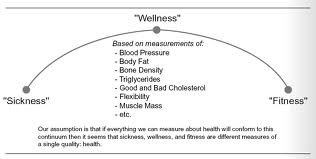

Greg Glassman’s sickness-wellness-fitness continuum is our guide: we want to look past the state of “just okay.” Shoot for the moon, land among the stars, and all that. But here’s what some miss: if you’re injured because your strength exceeded your skill, you’re no longer well. If you can deadlift-power curl 315lbs, but your clean technique falls apart at 135lbs, you’re going to break. This is why we have a skill bias: fitness equals better movement, not heavier movement. As teens in CrossFit Kids programs begin to blow past adults in their fitness and lifting, this message is finally starting to sink in.

Thus, half of our daily workouts focus on skill acquisition, or the skilled application of strength. If you’re lifting heavy weights with bad form, you’re not doing our workouts. I’ll stop beating that horse now.

The second half of a CrossFit group at Catalyst focuses on the metabolism of energy (“What Am I Gonna Do With All This Fitness?”)

Boot Camps focus on ground-n-pound: stick with calisthenics that drive the heart rate up, without consideration for energy pathways. While our METCON (METabolic CONditioning) may appear similar, there’s a lot more planning behind it. Programming METCON is more challenging than programming strength training. This is why Catalyst coaches explain the POINT of every metabolic workout during the group.

For example, the point of “Grace” is to spend 4-7 minutes in anaerobic metabolism. That means a very high heart rate. An athlete in our groups will be told to choose a weight that will allow for 30 cleans and jerks in 4-7 minutes. If that means 95lbs, great. If that means 155lbs, also great. CrossFit.com ‘prescribes’ 135lbs as a starting point for consideration, and to spur our audience toward objective measurement. If we’re all doing precisely the same thing, we can compare our score against others. This is also the primary reason for The CrossFit Games: let’s see how far fitness can be pushed, given that we’re controlling for squat depth and gymnastics skill.

When building METCON workouts, I have at least ten goals:

1. It’s fun. Like Jonah riding through the whale’s digestive tract. It may not feel fun at the time, but it makes for a great story later.

2. It’s different from the metabolic demands of the previous day.

3. Overall capacity isn’t limited by one tiny weak link, though it may be limited by a larger one. It’s okay if you can’t do any more pullups, but if you have to stop and hit a twelve-foot putt between 400m run intervals, your fitness may not be improving optimally.

4. The mind is primary. I want you to do two more reps than you feel like doing.

5. You’ll want to come back the next day. Sometimes, I leave my gym shorts at home on purpose on a rest day so that I’ll do my office work instead of jumping into the noon group. On the days when I find myself at Wal-Mart at 11:45, buying red shorts a size too small so that I can do the workout…it’s a winner.

6. I want to control some variables (the distance, the time) and have you fight for the others. That’s your score.

7. I want to show you that you’re improving. I have many blog posts about Bright Spots and how they help you stick with exercise for the long term. Read one here. This is why we have ‘named’ workouts: they’re a test.

8. I want you to be scared to eat poorly.

9. You expect the unexpected. The unknown isn’t scary when you’re exposed to it daily.

10. You’ll need to be coached. We’re not trying to trick you with acronyms like AMRAP and EMOM, but we ARE pressing the need to have eyes on you. Coaching is necessary, not negotiable. Our coaches get coached, their coaches get coached. Catalyst IS coaching, not equipment.

11. You get to do everything except swim. We run, we row, we swing, pull, jump, carry, lift, throw. We’re working on some other VERY cool stuff. If it makes you more fit, we want a piece of it.

During the METCON portion, your coach shifts from Caring Expert to Empathetic Cheerleader. We know what it’s like, yes, and we know what’s on the other side. We’ll tell you to clean up your squat even if you have 299 more to go, because we care that you’re getting better first, and faster second.

Finally, we debrief. Stretching is nice, but high fives and “Dude, you’re awesome!” is better. Many of us celebrate The Good Game every single day; it’s like having a game of pickup hockey, or golf, on your lunch break.

There’s a reason I’m not a magician: I like to share secrets. I like to show you, and then say, “Do it like this.” Our workouts aren’t random; even our new CrossFit Lite is planned far in advance, though it looks like a ‘bootcamp.’ This is how I do it. Start anytime, and get on the conveyor by showing up. It ain’t random.

Skip to content

Fill out the form below to get started

Take the first step towards getting the results that you want!