It’s good to be strong.

It’s better to be powerful.

Power is the ability to move things fast – including your body, or any external object.

We usually think of power in the gym as your ability to move a large load as quickly as possible – a barbell from the floor to overhead, or your body jumping from the floor onto a box. This is explosive power: maximum weight moving in minimum time. It’s the simplest version of the expression of power. This is the “power” we see in sport: an explosive backhand in tennis or a maximum throw of the javelin.

But power is relative, and in real life application, you have to be able to sustain power for different periods.

For example, if your car is stuck in a snowbank, you can’t just heave it out in one maximal thrust. You have to push it…and push it…and push it, probably for a minute or two without stop.

If you’re riding your bike up a hill, you can’t just turn the pedals over one time, as hard as possible, and then coast upward. You need to apply power to the pedals over and over – possibly hundreds of times or for up to 10 minutes.

And if you’re swimming or hiking for an hour, you might need to apply some power for the full 60 minutes. Obviously, you won’t put maximal power into every stroke or every step…but you’ll apply more power than you would just walking around.

Power is measured by a simple equation: P=W/t, where P is Power, W is Work, and t is time. Put simply, Power is the measure of work completed over a given time frame.

We really want to track how much work you can do over different time frames:

We want to know how much work you can do in an instant, like one max lift. In an emergency, I want you to be able to get off the mat and onto your feet fast…or lift the car off the child.

We want to know how much work you can do in a minute, because I want you to be able to move heavy snow away from your car fast.

We want to know how much work you can do in 5 minutes, because I want you to be able to catch your plane while dragging luggage and carrying a toddler.

We want to know how much work you can do in 10 minutes, because I want you to haul buckets when your neighbor’s basement is flooding.

And we want to know how much work you can do in 20 minutes, because most sports have a maximum play-time of 20 minutes without a break. Usually less, but you want to be ready to go.

That means we track – and sometimes graph – your power across broad time domains.

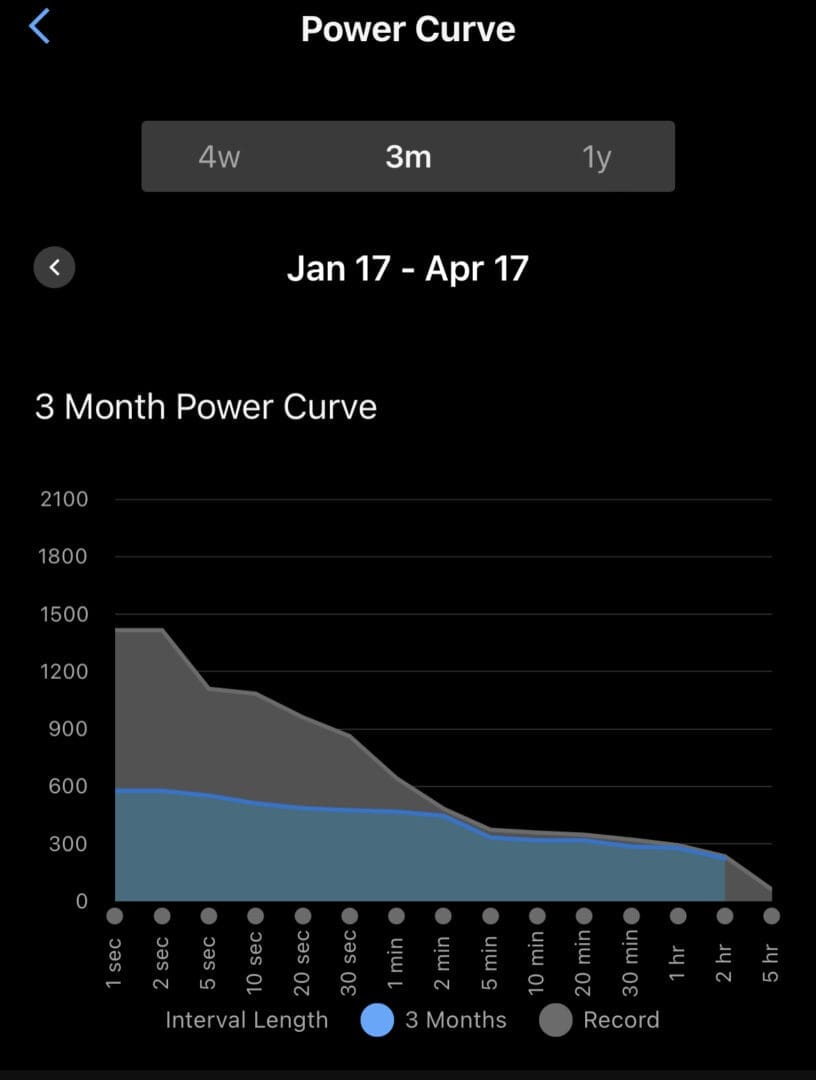

For an example, here’s my power graph, according to my Garmin app:

Power (in watts) is easy to measure on a bike with a power meter. That’s where these numbers come from. But the numbers don’t take into account my lifts – if we added my top clean or snatch, the numbers at the left side would go up. If we added my best weighted 2-hour hike, the numbers at the right side might come up a little.

The purpose of tracking is to find weaknesses. What kind of activity is likely to leave me stranded, helpless, or missing the cruise ship?

Looking at the graph above, you’ll see a very sharp drop between the 30-second and 5-minute mark. I can put out 900w for 30 seconds, but only 300w for 5 minutes. (The grey line, which is my all-time best outputs.) Looking at the blue line, the biggest drop is between the 2-minute and the 5-minute mark. That means any activity or emergency lasting longer than 2 minutes would have me give up before it’s done.

Now, my cycling coach sees that graph and thinks “If he hits a hill longer than 2 minutes long, he’s going to lose time.” So we work on improving power over two minutes in duration.

Where do different athletes fit on the curve? From Left to right:

Powerlifters and weightlifters (max lifts, done quickly)

Sprinters (max wattage over 10 to 15 seconds)

400m runners (max power over 1:00 to 1:30)

CrossFitters (max power over 5-15 minutes)

5k runners (max power over 15-30 minutes)

10 runners (max power over 35-60 minutes)

Cyclists (max power over 1-2 hours)

Marathoners (max power over 3-5 hours)

CrossFit uses workouts of varying lengths to try and raise this graph from one end to the other. And in general exercisers, that usually works (but also usually specializes on the left side of the graph, for various reasons–the ‘broad time and modal domains’ of most CrossFit programming isn’t very broad in time or modality, especially in the post-Glassman era.) People who want to improve at a sport, especially an endurance sport, will need to spend more time an an aerobic state.

Runners, on the other hand, spend too much time at the right end of the graph. While a CrossFitter’s “endurance” is relative to their sport (usually it’s 20 minutes or less,) a runner’s “power” is relative to their own sport. Tell a distance runner to sprint, and most will struggle to speed up much above their 5k pace. The answer is to train the different domains of power separately, depending on your coach’s prescription.

It’s also interesting to note that the power graph correlates strongly to the metabolism of energy.

If you look at my graph again, that loss of power between 2 and 5 minutes has several causes. One is the shift from using carbs for energy to using a mixture of carbs and fats for energy. Making that a smoother transition (or increasing the amount of power I can put out long-term) would require better utilization of fats for energy for longer. It’s as if I’m switching from gas to diesel power at that point, and it takes a moment for the diesel motors to ramp up to the level of the gasoline engine’s production.

Here’s the bottom line: there are times in life when you need to be strong. Most of these times also require you to be fast: to react and jump out of the way, jump under something or over something, push fast, carry rapidly, or even throw. Strength is necessary for all of these, but the real requirement is power. Are you doing enough?

Ready to start with a coach? Click here to book a No-Sweat Intro, and get your plan together!